COLOSSEO DI ROMA TICKETS

Discover the history of Rome with direct access

- Skip the line

- Duration 3 hours

- Audio guide; ENG, SPA, FRA, DEU, POR, ITA, RUS, JPN, ZHO

- Guided Tour

- Minimum age +18

- The voucher is accepted on the mobile

- Wheelchair accessible

- Discount for children under 18 years old

Welcome to the Colosseo of Roma

A Timeless Icon of History and Architectural Grandeur

International prestige

Discover one of the legendary Seven Wonders of the World!

+ 12 million visitors per year

Enjoy a historical site that is unique in the world.

The Roman Colosseum is one of the most iconic monuments in the world and one of the seven wonders of the modern world. If you plan to visit it, here are some fascinating facts and how to get your tickets in the best way.

A Little History

Built in the 1st century A.D. under Emperor Vespasian and completed by his son Titus in 80 A.D., the Colosseum was the largest amphitheater in Ancient Rome. With a capacity for over 50,000 spectators, it was the epicenter of entertainment with gladiators, naval battles and exotic spectacles.

Curiosities of the Colosseum that will surprise you

1. It was not always called Colosseum

Originally, its name was “Flavian Amphitheater” in honor of the Flavian dynasty. The name “Colosseum” comes from a colossal statue of Nero that stood near the amphitheater.

2. It could be filled and emptied in minutes

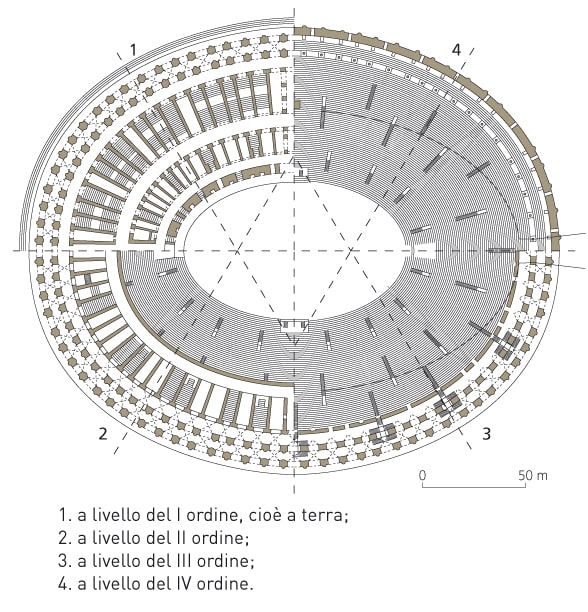

Thanks to its advanced architecture, the Colosseum’s 80 entrances allowed thousands of spectators to enter and leave in minutes, a design that still inspires modern stadiums today.

3. Ancient naval battles inside the Colosseum

In its early years, a flooding system was used to recreate naumachias (naval battles), with ships and actors fighting in the water.

An amphitheater with a retractable roof

The Colosseum had an awning system called “velarium” that protected spectators from the sun and bad weather. It was operated by expert sailors.

Colosseum Opening Hours

Colosseum: opens at 8:30 AM

Roman Forum & Palatine Hill: open at 9:00 AM

Colosseum Closing Hours

30 March – 30 September 2025: 7:15 PM

1–25 October 2025: 6:30 PM

26 October 2025 – 28 February 2026: 4:30 PM

Closed: 25 December 2025 & 1 January 2026

Dear visitor, welcome to the Parco archeologico del Colosseo.

RULES AND RESTRICTIONS FOR SAFETY, CONSERVATION, AND DECORUM

It is strictly forbidden to:

– write on the walls or on the artefacts

– damage or remove archaeological material

– light fires

WHOEVER WRITES ON THE WALL DAMAGES DESTROYS DISPERSES DETERIORATES ARCHAEOLOGICAL AND MONUMENTAL ASSETS IN THE ARCHAEOLOGICAL PARK SHALL BE PUNISHED BY IMPRISONMENT OF 2 TO 5 YEARS AND A FINE RANGING FROM EUR 2.500 TO EUR 15.000 (art. 518 duodecies of the Penal code)

RULES OF CONDUCT

Following the natural boundaries of the ancient Palatine, Velian and Oppian Hills, and including the valley of the Forum and the Colosseum, the Parco covers a vast archaeological area which is mostly situated on uneven terrain. Many areas are accessible via historic walking paths which are often rocky, uneven and which include ancient steps that are not always level. Furthermore, the Flavian Amphitheater contains some very steep steps and paths which are at times rough and uneven.

During your visit, you are kindly requested to pay careful attention to your footing along walking paths and to observe the following rules.

- Areas closed to the public are off-limits to visitors

- No walking or loitering outside of marked walking paths

- No leaning over railings or banisters

- No running

- Appropriate footwear is advised (high heels and flip-flops are not recommended)

- Children must be supervised and held by the hand at all times

- Clothing appropriate to the formal setting of the site is required, prohibiting ceremonial dresses, masks, period costumes and any other fancy dress undignified for such places

- Visitors are asked to respect designated walking paths

- Please pay attention to the pavement along walking paths at all times

- Visitors may only follow walking paths open to the public

- Visitors are advised to exercise caution on uneven steps

- Visitors shall assume full responsability regarding choice to access those area with more difficult footing (inclined footpaths, stairways with particularly steep steps). PArCo administration therefore accepts no liability in the event of accidents or injuries.

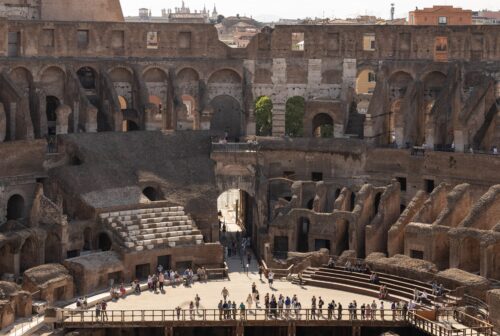

he Flavian Amphitheatre, more commonly known as the Colosseum, stands in the archaeological heart of Rome and welcomes large numbers of visitors daily, attracted by the fascination of its history and its complex architecture.

The building became known as the Colosseum because of a colossal statue that stood nearby. It was built in the 1st century CE at the behest of the emperors of the Flavian dynasty. Until the end of the ancient period, it was used to present spectacles of great popular appeal, such as animal hunts and gladiatorial games. The building was, and still remains today, a spectacle in itself. It is the largest amphitheatre in the world, capable of presenting surprisingly complex stage machinery, as well as services for spectators.

A symbol of the splendour of the empire, the Amphitheatre has changed its appearance and its function over the centuries, presenting itself as a structured space but open to the Roman community.

In 438, with the abolition of the gladiatorial games by order of Valentinian III, the amphitheatre underwent a slow and steady decline. In the Middle Ages and Renaissance it even became a quarry for building materials, part of it being used for the construction of St. Peter’s Basilica, and a shelter for animals and containing craft workshops and houses, while it was also Christianised over a long lapse of time. After the Romantic period, when the charms of the ruin attracted writers and artists, it soon became a place of systematic excavations and restoration work.

Today the Amphitheatre is a monument to works of art and human ingenuity that have survived the centuries. It still appears as a welcoming and dynamic structure, offering a broad panorama of its interior spaces as well as striking views of the city when you gaze out from the external arches.

Periodically it hosts temporary exhibitions related to the themes of antiquity and its relationship with contemporary life, as well as modern spectacles. The significance of these events and experiences has made the Amphitheatre a place that is renewed every day, rich in significance for all and capable of telling stories that will interest everyone.

The Forum was originally covered by a swamp. It was only in the late 7th century BCE that the valley was reclaimed and the Roman Forum began to take shape. It was destined to remain the centre of public life for over a millennium.

The various monuments were built through the centuries: first the buildings for political, religious and commercial activities, then during the 2nd century CE the civil basilicas, used for judicial activities. Already at the end of the republican age, the ancient Roman Forum had become insufficient to serve as the administrative and representative centre of the city.

The various dynasties of emperors added only prestigious monuments: the Temple of Vespasian and Titus and that of Antoninus Pius and Faustina, dedicated to the memory of the deified emperors, and the monumental Arch of Septimius Severus, built at the western end of the Forum in 203 CE to celebrate the emperor’s victories over the Parthians.

The last great development was carried out by the emperor Maxentius in the early years of the 4th century CE, when the temple dedicated to the memory of his son Romulus and the imposing Basilica on the Velian Hill was erected. The last monument built in the Forum was the Column erected in 608 CE in honour of the Byzantine emperor Phocas.

After this date, part of the area was gradually buried under silt, turning to meadow and taking the name of the Campo Vaccino, but some monuments survived by being converted into churches. The Iulia Curia became the church of Sant’Adriano; part of the temple of Antonino and Faustina was transformed into the church of San Lorenzo in Miranda, while the temple of Romulus became the church of the Santi Cosma and Damiano. The church of Santa Maria Nova was erected in the 9th century in one of the cells of the Temple of Venus and Roma. In the 16th century, the church of San Giuseppe dei Falegnami was constructed over the Mamertine Prison, the medieval name of the Tullianum, an ancient jail built by Ancus Marcius (640–616 BCE), where Catiline and Vercingetorix were imprisoned. According to an unproven medieval tradition, St. Peter was also held prisoner in it. Finally, in the 17th century, the church of Santi Luca e Martina was rebuilt on the ruins of the Secretarium Senatus.

It was not until the unification of Italy that the first systematic excavation work was carried out in the area.

The Palatine hill preserves the remains of Iron Age settlements connected with the earliest core of the city of Rome. The hill was home to important civic cults, including the Magna Mater (Cybele) and, between the 2nd and 1st centuries BC, it became the residential district of the Roman aristocracy, with elegant houses characterised by exceptional painted and paved decorations, such as those preserved in the House of the Griffins. Augustus symbolically chose the hill as the site of his own house, which consisted of several buildings, including the House of Livia. Later the hill became the site of the imperial palaces: the Domus Tiberiana, the Domus Transitoria and then the Domus Aurea, and finally the Domus Flavia, divided into a public and private sector, the latter being known as the Domus Augustana. From their complex and partly overlapping plans, it is possible to understand how the different residences were connected to each other partly by underground passages, often richly decorated, of which the Neronian Cryptoporticus remains one of the best preserved examples. The presence of the imperial residences on the hill gave rise to a process of identification. In this way the toponym Palatium came, in modern languages, to mean a royal palace.

At the Renaissance, the Palatine became the property of aristocratic families who built villas and planted vineyards and gardens on it. Today there still survives a part of the fascinating Horti Farnesiani, on the upper part of the hill, as well as the Loggia Stati-Mattei with its pictorial decorations. Some of the most significant artefacts found in the excavations of the site since the 16th century are now displayed in the Museo Palatino.

After the devastating fire of 64 AD, which destroyed much of the centre of Rome, the emperor Nero began building a new residence, which for pomp and splendour went down to history by the name of the Domus Aurea.

Designed by architects Severus and Celer and decorated by the painter Fabullus, the palace consisted of a series of buildings separated by gardens, woods and vineyards and an artificial lake, which lay in the valley where the Colosseum stands today. The main nuclei of the palace were on the Palatine Hill and Oppian Hill and they were famous for the sumptuous decoration in which gold and precious stones were added to stuccos, paintings and coloured marbles. The huge complex included bathrooms with normal and sulfurous water, several banqueting rooms, including the famous coenatio rotunda, which rotated on itself, and a huge vestibule that housed the colossal statue of the emperor in the garments of the Sun God.

After Nero’s death his successors decided to erase all traces of the emperor and his palace. The luxurious chambers were deprived of their cladding and sculptures and filled in with earth up to the vaults to be used as the substructures for other buildings.

The parts that can be visited today are those on the Oppian hill: these areas were probably used for holding festivities and banquets. After they were buried, they remained unknown until the Renaissance. Only then, after some chance discoveries, did artists with a passion for antiquities, such as Pinturicchio, Ghirlandaio, Raphael and Giulio Romano, begin to explore what they thought of as “underground grottoes”, to copy the decorative motifs in them. Because of their location, they were called “grotesques.” Even today the term “grotesque painting” is used to indicate a genre, very common above all in the 16th century, which imitates the patterns of Roman wall decoration, reworking and reinterpreting them in playful and imaginative ways.